This newsletter is going to explain the new Olympic marathon qualifying system

Basically, it sucks.

Hi there! I originally wrote this primer in March 2019, when the new standards were announced.

This post was last updated on Jan. 26, 2020.

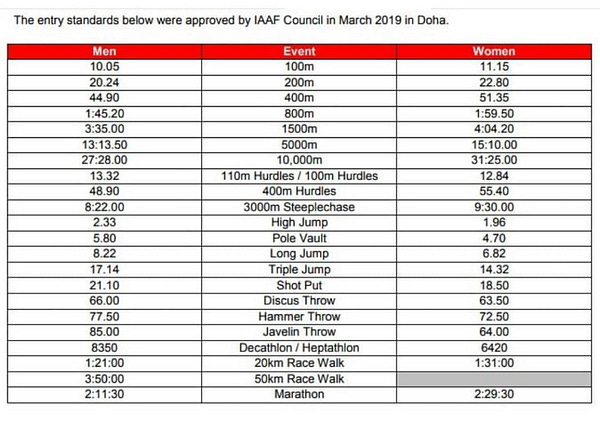

There are new Olympic qualifying standards for track & field

IAAF announced a new qualifying process for the Olympics in March 2019.

The old way to qualify? Run the Olympic standard and be invited by your country to participate.

The new way to qualify? Let me explain….

The big changes are:

They cut the number of athletes who will participate in each event

They made the qualifying times waaaaaaaaay harder

They introduced a multi-tier qualification system, using qualifying times, marquee event performances and IAAF world rankings.

IAAF expects to fill about half the field with time qualifiers and half the field the other ways.

I’m going to focus on the marathon for this explainer.

Both the men’s and women’s marathons will now have 80 athletes each, down from 155 men and 156 women in 2016.

The qualifying period for the marathon for the 2020 Olympics is January 1, 2019 to May 31, 2020. For other track & field events it’s May 1, 2019 to June 29, 2020.

Previously, athletes had to hit a qualifying standard — 2:19 for men, 2:45 for women — and then be selected by their country’s governing body for their Olympic team (In Canada’s case, Athletics Canada). Each country was limited to three athletes.

Canada, however, set a much tougher qualifying standard: 2:12:50 for men and 2:29:50 for women. If you hit the Olympic standard but not the Canadian standard? Too bad, no Olympics for you. Hit the Canadian standard? Well, then you need to be one of the top three fastest Canadians to hit that standard, then you’re in. BUT since the Canadian standards were so hard, hitting it pretty much meant you were automatically going to the Olympics. (In 2016, there was a “competitive readiness clause” but I’m not going to get into that now.)

What does this new system mean for marathoners wanting to go to Tokyo? How could they make it to the Olympics? It’s complicated, but let’s see if this helps.

OPTION #1: Run the new, super fast standard

The new IAAF standards are faster than Canada’s old standards. Men must run 2:11:30 and women must run 2:29:30.

Could a Canadian qualify this way? The fast ones can

Rachel Cliff ran the standard when she broke the Canadian record, running 2:26:56 at the Nagoya Women’s Marathon in Japan.

Only two other Canadian women have run faster than the new standard since 2006 — Lanni Marchant and Krista DuChene, but neither has since 2015 — and only six Canadian women have ever run that fast.

There are a handful of Canadian women within minutes of this new standard. Lyndsay Tessier ran 2:30:47 at Berlin, Kinsey Middleton ran 2:32:09 in Toronto, and Malindi Elmore ran 2:32:11 and Sasha Gollish ran 2:32:52 in Houston.

On the men’s side, Cam Levins, Reid Coolsaet and Eric Gillis have all run faster than this new standard before. Cam did it in 2018 in his marathon debut, Reid’s done it six times, but last did it in 2016 and Eric’s done it three times, but most recently in 2015.

Only eight Canadian men have ever run under the new standard, and Cam is the only one to have come anywhere close to it in the past two years.

OPTION #2: Finish top 10 at a World Marathon Major

Finish top 10 at Boston, London Berlin, Tokyo, Chicago or New York during the qualifying period and you qualify for the Olympics.

Could a Canadian qualify this way? Maybe, with the right race and bit of luck

In 2018, Krista DuChene finished third and Reid Coolsaet finished ninth at Boston (which isn’t really representative of how they could place in any other year, as the weather was insane). Rachel Cliff finished 11th at Berlin, just missing the top 10.

No other Canadian landed anywhere near the top 10 at the other majors in 2018. But it’s happened before: Lanni Marchant finished seventh at NYC in 2016.

How do the most recent world majors results look in light of this new system? Let’s see.

Men:

Tokyo 2019: 10th place was 2:12:21, 9/10 ran below the standard

Boston 2018: 10th place was 2:27:50, 0/10 ran below the standard

Boston 2017 (Because 2018 was such an outlier): 10th place was 2:15:28, 3/10 ran below the standard

London 2018: 10th place was 2:12:09, 8/10 ran below the standard, 9th place missed it by two freaking seconds.

Berlin 2018: 10th place was 2:13:09, 8/10 ran below the standard

Chicago 2018: 10th place was 2:08:41, top 11 ran under the standard

New York 2018: 10th place was 2:13:08, 5/10 ran under the standard

Using the data from Tokyo 2019 and the other majors’ 2018 results, 40/60 ran under the new standard and 20 qualified running slower than the standard.

Women:

Tokyo 2019: 10th place was 2:31:39, 8/10 ran below the standard

Boston 2018: 10th place was 2:48:29, 0/10 ran below the standard

Boston 2017 (Because 2018 was such an outlier): 10th place was 2:33:26, 6/10 ran below the standard

London 2018: 10th place was 2:32:28, 8/10 ran below the standard

Berlin 2018: 10th place was 2:27:29, the top 11 finishers ran below the standard

Chicago 2018: 10th place was 2:34:53, 4/10 ran below the standard

New York 2018: 10th place was 2:30:47, 8/10 ran below the standard

Using the data from Tokyo 2019 and the other majors’ 2018 results, 38/60 ran under the new standard and 22 qualified running slower than the standard.

Important to note, the IAAF document said majors “during the qualification period” which means the following world majors should count:

Tokyo 2019

Boston 2019

London 2019

Berlin 2019

Chicago 2019

NYC 2019

Tokyo 2020

Boston 2020

London 2020

OPTION #3: Finish top five at a IAAF Gold Label marathon

Marathons around the world are given a ranking by the IAAF. There’s a bunch of different factors that go into getting a Gold Label, including the elite field, road closures, environmental impact, how the race is timed and measured, and more.

There are currently 36 Gold Label marathons, including the six world majors.

Canada has two: Ottawa and Toronto.

Could a Canadian qualify this way? There’s an outside shot, but it’s damn hard to run top 5 at these races without running the standard

In 2018, here’s how the Canadian Gold Label races went down:

Ottawa: Top Canadian male was Tristan Woodfine, finishing ninth in 2:18:54. The fifth place male finisher was nearly seven minutes faster, running 2:11:15. The top Canadian female was Kate Tuohy, running 2:45:06 for a eighth place finish. The fifth place woman was 10 minutes faster, running 2:35:04.

In Ottawa, the top five male finishers qualified by time and placement. The fourth and fifth place female finishers qualified by placement only, and the top three female runners place qualified by both time and place.

Toronto: Cam Levins finished fourth overall, running 2:09:25. The fifth place finisher behind him ran 2:09:52. On the women’s side, Kinsey Middleton came seventh with her 2:32:09 time. The fifth place woman was five minutes faster, running 2:26:58.

In Toronto, Cam would have qualified by time and placement, as would have all top five male finishers and top five female finishers.

But Kinsey would not have qualified at all. (This becomes important later, keep reading.)

Here are the other fifth place times + number of time qualifiers in 12 other Gold Label races for reference.

Men

Dubai 2019: 5th place was 2:05:18, top 10 ran the standard

Paris 2018: 5th place was 2:08:20, top 12 ran the standard

Vienna 2018: 5th place was 2:12:03, top 3 ran the standard

Madrid 2018: 5th place was 2:11:16, top 6 ran the standard

Prague 2018: 5th place was 2:10:26, top 6 ran the standard

Gold Coast 2018: 5th place was 02:11:42, top 4 ran the standard

Sydney 2018: 5th place was 2:19:53, no one ran the standard (This seemed slow, but is consistent with the 2017 results)

Cape Town 2018: 5th place was 2:12:39, top 4 ran the standard

Libson 2018: 5th place was 2:08:18, top 9 ran the standard

Amsterdam 2018: 5th place was 2:06:24, top 10 ran the standard

Frankfurt 2018: 5th place was 02:07:34, top 8 ran the standard

Fukuoka 2018: 5th place was 2:10:31, top 7 ran the standard

Breaking down these results: 61 out of the 70 athletes qualified this way in the above sample (14 races) ran the standard, meaning qualified and ran slower than the standard.

Those are… bad odds. And the odds are worse if you toss the outlier Sydney marathon sample: 4/65 qualified without running the standard. To be fair, I didn’t look at every race (I ran out of time), so there might be a gem or two out there, but the trend above is pretty clear.

Women

Nagoya Women’s Marathon 2019: 5th place was 2:23:52, top 18 (including Rachel Cliff) ran the standard

Dubai 2019: 5th place was 2:25:59, top 7 ran the standard

Paris 2018: 5th place 2:23:43, top 8 ran the standard

Vienna 2018: 5th place was 2:32:47, top 3 ran the standard

Madrid 2018: 5th place was 2:47:15, no one ran the standard

Prague 2018: 5th place was 2:30:50, top 3 ran the standard

Gold Coast 2018: 5th place was 2:30:19, top 3 ran the standard

Sydney 2018: 5th place was 2:45:30, no one ran the standard

Cape Town 2018: 5th place was 02:31:34, only the winner ran the standard

Libson 2018: 5th place was 2:34:10, top 3 ran the standard

Amsterdam 2018: 5th place was 2:23:45, top 8 ran the standard

Frankfurt 2018: 5th place was 2:22:39, top 13 ran the standard

Breaking down these results: this qualifying route proves to be easier for women than men.

46 out of the 70 athletes who qualified this way in the above sample ran the standard, meaning 24 qualified and ran slower than the standard.

OPTION #4: Finish top 10 at the world championships in Doha

The IAAF track & field world championships are held every two years. 2019 is an “on” year, with the worlds taking place in Doha, Qatar from September 28 to October 6.

The qualifying standards for that race were 2:16 for men and 2:37 for women or by finishing top 10 at a Gold Label race. (You can read the PDF with the standards for yourself here.) You can qualify for worlds in between March 7, 2018 and September 6, 2019.

Could a Canadian qualify this way? Uhhh…. probably not

The top Canadians at the 2017 world championships were Thomas Toth, who placed 54th in 2:23:47, and Tarah Korir, who was 51st in 2:44:30.

The 10th place times at London in 2017 were 2:29:01 for women and 2:12:41. All top 10 women ran the standard and six of the top 10 men did.

London is not the same climate as Doha, which will potentially impact performances. At Rio in 2016 — another hot race with a comparable field — Canadian Eric Gillis finished 10th, running 2:12:29. Only the top six in the men’s race at the 2016 Olympics hit the 2020 standard.

The women’s race in Rio was much slower, with no competitors running a time that would qualify them for the 2020 Olympics. But the top Canadian was Lanni Marchant, she placed 24th and ran 2:33:08.

Doha’s going to be hot AF. If you want to do well there, you need to prepare for it. And then to get top 10, you’re going to need an amazing performance a la Eric Gillis at the 2016 Olympics. So it’s not impossible, but I’d say not worth it unless running a world championship is really important to you as a runner.

(Side note: It’s a little bonkers that the new standard is so hard that only 6 out of 311 athletes ran it AT THE OLYMPICS.)

OPTION #5: Be ranked high enough in the world to get invited

The IAAF will then fill the rest of the Olympic marathon field with athletes who are ranked high enough within their very complicated ranking system, as long as there is space for them.

But with only 80 spots in both the men’s and women’s marathon, it’s not a qualifier to count on.

Could a Canadian qualify this way? Maybe, but it’s a headache and a waiting game

In the simulation IAAF provided to member countries, Cam Levins — the fastest Canadian man of 2018 — was ranked 173 out of 535. Rachel Cliff — the fastest Canadian woman of 2018 — was ranked 210 out of 392.

No other male Canadians made the spreadsheet but a handful of women did:

#234: Kinsey Middleton

#237: Lyndsay Tessier

#252: Leslie Sexton

#301: Dayna Pidhoresky

#307: Melanie Myrand

#337: Krista Duchene

When you eliminate athletes above them who are not eligible due to the three-athletes-per-country rule, Cam moves up to #36 and the women move up to the following places:

#51: Rachel Cliff

#58: Kinsey Middleton

#59: Lyndsay Tessier

And that’s three Canadians, so no one else would make it.

So, in this working example, Rachel has already qualified with her time and MAYBE Kinsey and Lyndsay make it to the Olympics this way. It depends on how many runners qualified one of the other ways and how many open slots are left to fill the field.

That’s stressful, and a bad way to rely on getting into the Olympics.

What does this mean for Canadian marathoners?

If 2018 was to yield our Olympic team based on these new standards, it would be Cam Levins (time qualifier @ Toronto) and Reid Coolsaet (Boston placement) on the men’s side and Rachel Cliff (time qualifier @ Berlin) and Krista DuChene (Boston placement) on the women’s side and maybe Kinsey Middleton (IAAF ranking), depending on how the rankings shake out.

This team is comparable to our 2016 marathon team of Krista DuChene, Lanni Marchant, Eric Gillis and Reid Coolsaet.

Athletics Canada said they would honour the new qualifying process for 2020 — there’s no extra Canadian qualifying layer anymore. If a Canadian qualifies one of the above ways, they are considered eligible, then they need to be one of the three athletes invited by Athletics Canada to participate in the Olympics.

Wasn’t there a big announcement earlier this year, though? About the Toronto marathon and the Olympics?

Yep. It was previously announced that the Canadian champions of the Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon would auto-qualify if they hit the not-yet-announced IAAF Olympic standard.

When the qualifying times were 2:19 and 2:45, this was pretty much a sure bet. But now that the qualifying times are fasssssst, it’s not anymore: the only Canadian who would have qualified since 2016 is Cam Levins.

Just being top Canadian isn’t going to cut it anymore.

The Canadian STWM champions would now have to finish under the new qualifying time OR in the top five overall in the race to nab an Olympic spot with their Toronto performance.

They do, however, have the entire qualifying window to achieve the standard. So if the top Canadians don’t walk away with the standard at Toronto, they have until May 31, 2020 to get it.

In the 2018 Toronto example, Cam would be fine, but Kinsey would have needed to run a spring marathon and go for the standard to secure her spot before the qualifying period closed.

In 2019, both Canadian champs — Trevor Hofvauer and Dayna Pidhoresky — ran under the time standards, so this was a non-issue.

Who has qualified so far?

As of Jan. 26, 2020, Malindi Elmore, Rachel Cliff, Lyndsay Tessier, Dayna Pidhoresky and Trevor Hofbauer have qualified for the 2020 Olympics in the marathon.

Malindi Elmore ran 2:24:50 at the Houston marathon in January 2020, setting a new Canadian record in the process.

Cliff ran 2:26:56, which is below the standard, in at the Nagoya Women’s Marathon in Japan.

Tessier placed ninth at the world championships in Doha, Qatar. She ran 2:42:03, but top 10 at worlds get the standard, regardless of time.

Pidhoresky ran 2:29:03 at the Toronto Waterfront Marathon to win the Canadian national championships and score the time standard. As the national champion, she will automatically be selected for the team.

Canada is allowed to send only three athletes of each gender. If any more women qualify, Athletics Canada will have to select two athletes from the qualified women to go to Tokyo alongside Pidhoresky.

Hofbauer ran 2:09:51 to win the Canadian national championships and score the time standard. As the national champion, he will automatically be selected for the team. No other Canadian me have qualified.

There are more running distances than the marathon, what does it mean for them?

No good, very bad news.

The standards are harder, the fields are smaller.

As an example, Natasha Wodak’s Canadian record at the 10,000 is 15 seconds slower than the new standard.

Which means if Wodak wants to run in the Olympics, she’s gotta to set a new national record or qualify another way. But rankings require consistent performance over a set period of time in the right races.

How to get in to the right races now matters. Performing well at the right races matters even more.

What does this all mean?

It does mean a longer qualifying window and more value being placed on head-to-head competition, which is good, but overall it means fewer Olympians and fewer opportunities for athletic development.

And it will be harder to find good news stories and media attention out of the qualification process because, well, “hey, they won the Olympic trials/national championship in their country and that gives them IAAF points, but they didn’t run the IAAF standard so they miiiiiiiiiight go to the Olympics but we won’t know for four months” is a bad headline.

The new system is not great. The standards are difficult to achieve and the system is so confusing I just wrote a 3,000 word newsletter explaining it all and I’m not entirely confident I got everything right.