Let's look at every Olympic running medal Canada has won since 1896

And it's been 24 years since Donovan Bailey won Olympic gold and told Sports Illustrated that Canada had problems with racism

Hello -

I hope you all enjoyed the long weekend. I forgot it was a long weekend when I was putting together last week’s newsletter because pandemic time is real. So if you were expecting this issue yesterday, I’m sorry for forgetting to flag this schedule change and thank you for your patience.

This week, I roundup some news and podcasts and look at the legacy of Donovan Bailey and how, for 24 years, he’s been speaking out about anti-Black racism in sports and in Canada. But I kick things off with a look at how Canada has done in running events at the Olympics, historically.

It’s a long issue, so it may cut off in your email browser. If that happens, you can read it online here.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’m so grateful the readership of Run the North continues to grow during a time of so much uncertainty and so little running news.

OK, let’s get to it!

— Erin @ Run the North

A brief history of Canadian running at the Olympics

The 2020 Olympics were supposed to take place this summer, July 23 to Aug. 7. In honour of that, I decided to look back at Canada’s track & field history at the Olympics since their inception in 1896.

What follows is an overview of what medals we won, who won them and an attempt to find interesting trends and narrative threads from the 124-year history of the Olympic Games and Canada’s place within them.

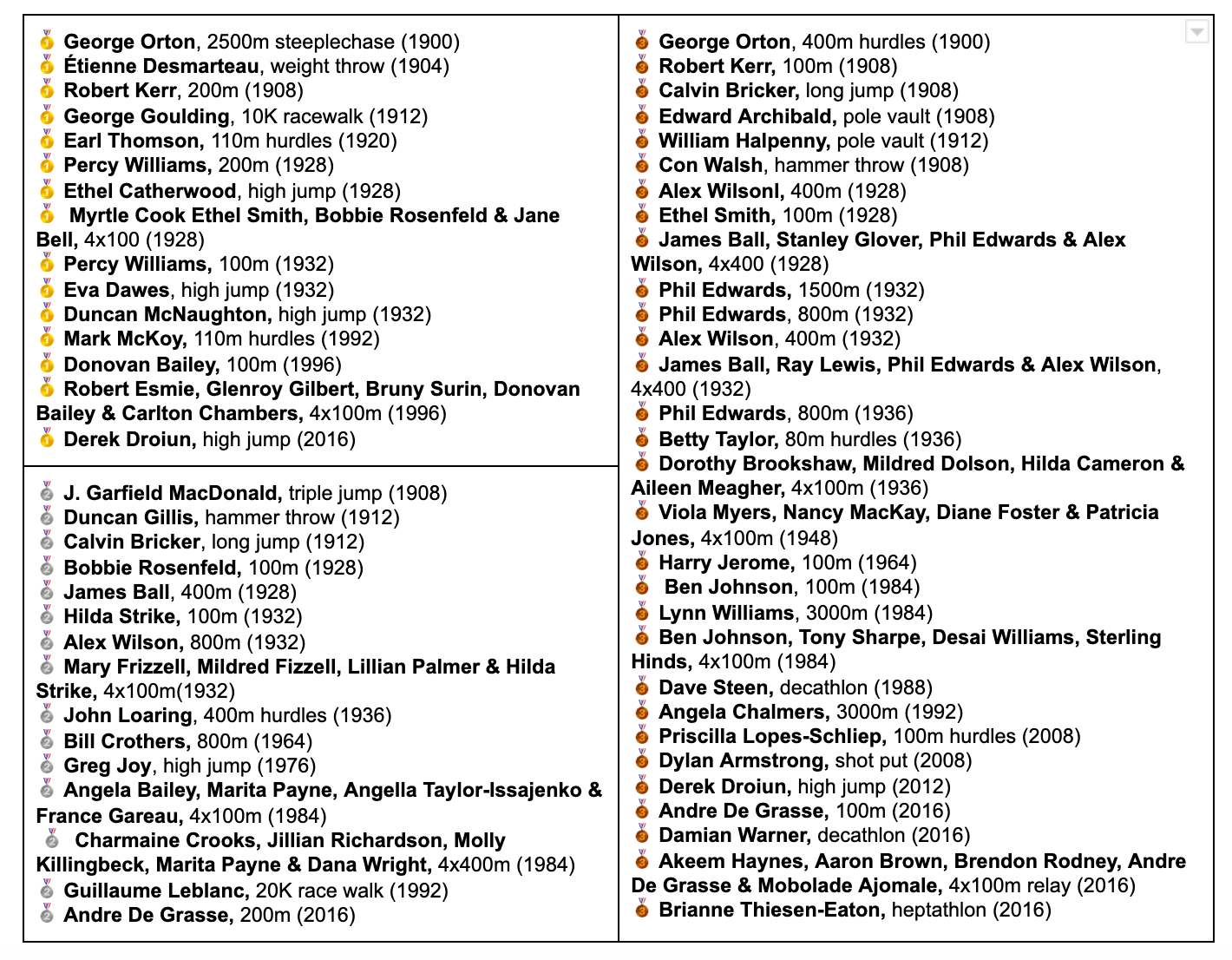

Canada has won 60 athletics medals since competing at the Olympics for the first time in 1900: 15 gold, 15 silver and 30 bronze. 42 are running medals, 14 are field medals and four are combined events medals.

I got almost all the following information from Canada’s Olympic Committee website. If it’s from somewhere else, I linked to it.

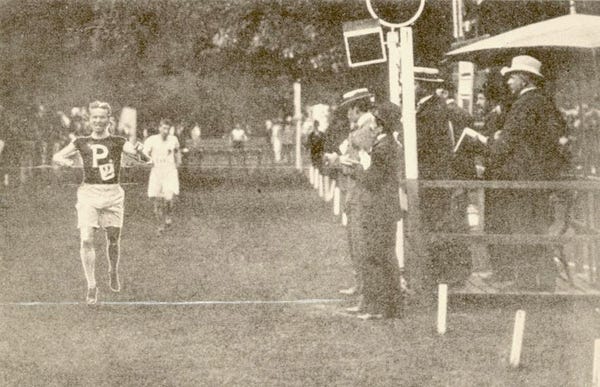

Canada’s first Olympic medallist, George Orton

George Orton became Canada’s first medallist when he took home gold in the 2,500m steeplechase and bronze in the 400m hurdles.

He also retroactively won bronze because in 1900, the Olympics gave a silver medal to the winners, a bronze medal to second place and third place got nothing. They changed to the gold, silver, bronze format in 1904 and retroactively awarded the new medal system to past Olympians.

Nationalities weren’t tracked for the Olympics until 1908, and George was mistakenly identified as American, and his medals were credited to the U.S. until 1977.

George’s gold in the steeplechase is the only medal Canada has won in this event, at any distance.

George was born in 1873 in rural Ontario. He was paralyzed when he fell out of a three at three years old, and didn’t walk again until he was 10. After his Olympic career, he would move to Pennsylvania and be instrumental in introducing hockey to the state.

It’s quite a story and if you want to learn more, I recommend you check out the book The Greatest Athlete (You’ve Never Heard Of) by Mark Hebscher. His Olympics bio is here if you want a briefer take.

Other early stars

Robert Kerr was another early star, winning gold in the 200m and bronze in the 100m in 1908.

Robert was originally from Ireland and came to Canada in 1887, when he was five years old. Over the course of his career, he would set six Canadian records. After his athletics career, he remained very involved in Canadian sports and was instrumental in establishing the British Empire Games (now known as the Commonwealth Games). You can read more in his Olympics biography.

Earl Thomson won gold in the 110m hurdles in 1920.

Earl was born in Saskatchewan in 1895, but moved to California with his family as a boy. He applied to represent the U.S. at the 1920 Olympics, but this request was denied, so he competed for Canada. He became a track coach after his athletics career. You can read his Olympics bio here.

Canada also won several field medals in this era:

🥇Étienne Desmarteau, weight throw (1904)

🥈J. Garfield MacDonald, triple jump (1908)

🥈Duncan Gillis, hammer throw (1912)

🥈Calvin Bricker, long jump (1912)

🥉Calvin Bricker, long jump (1908)

🥉Edward Archibald, pole vault (1908)

🥉Con Walsh, hammer throw (1908)

🥉William Halpenny, pole vault (1912)

Canada’s racewalking history

George Goulding would win Canada’s first racewalking medal, when he won silver in the 10K event in 1912.

George competed in the 1908 and 1912 Olympics. He was a marathoner, competing in the 1908 marathon, but took to racewalking and entered the 3,500m and 10 mile racewalks that Olympics, in addition to running the marathon.

1912 marked the first year for the 10K racewalk, and George took home the gold in that race. George became one of the dominant racewalkers in the world, you can read more in his Olympics bio.

There have been several distances at the Olympics over the years, but men now compete in two long distances: 20K and 50K. In 1992, women’s racewalking was added, but women only compete in the 20K.

Since 1912, Canada has won only more racewalking medal: Guillaume LeBlanc won silver in the 20K racewalk in 1992.

Guillaume is from Rimouski, Quebec, and he competed in the racewalk in the 1984, 1988 and 1992 Olympics. In 1984, he placed fourth in the 20K and DNFed the 50K. In 1988, he placed 10th in the 20K and did not compete in the 50K. In 1992, he was disqualified from the 50K. But he earned silver in the 20K.

This 1992 Macleans interview with Guillaume and his wife right after his medal is pretty great:

While he looked ahead to the 50-km race on Aug. 7, his excited wife, Manon Boudreau, was answering a constantly ringing phone in Rimouski. The couple has a two-year-old daughter, AnneMarie, and Boudreau, 27, was expecting their second child later this month. The timing, she said, was no accident. “I had miscarried,” she explained, “and we wanted another baby before Anne-Marie got too much older. So we discussed whether to wait until after the Games or whether to have one now, and we decided to go ahead. Guillaume called me last night and said: ‘I hope if I do well that you won’t go ahead and have the baby without me.’ But I told him that if it happened, it would be a good sign for the baby.”

Evan Dunfee was briefly third in the 50K racewalk in 2016, when the third place racewalker was temporarily disqualified. He was reinstated, pushing Evan back to fourth, and Evan decided to not pursue an appeal. Evan is a medal contender for the 50K in 2020(1).

The golden age of Canadian track at the Olympics

Canada’s best athletics performance at the Olympics came in the years 1928 and 1932. In 1928, Canada won eight athletics medals. In 1932, we won nine. 1936 was a solid year as well, with Canada taking home four medals.

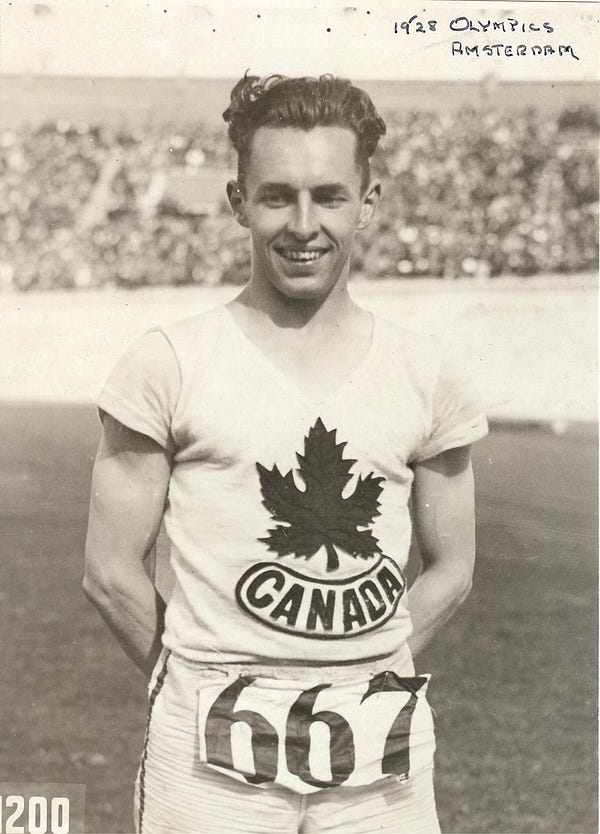

This period saw the rise of several stars, including Percy Williams.

Percy won double gold in 1928, winning the 100m and 200m.

Percy was born in Vancouver in 1908. He broke onto the world track scene at the 1928 Olympics with his double gold performance. His victories were unexpected and he returned to Canada a hero. He would set the world record in the 100m in 1930, but an injury later that same year would derail his career. He recovered enough to participate in the 1932 Olympics, and retired shortly after. You can read his Olympics bio here.

With five Olympic medals to his name, Phil Edwards is Canada’s most successful track athlete.

Over the course of three Olympics, he won five medals, all bronze: the 4x400m relay in 1928 and 1932, the 1,500m and 800m in 1932 and the 800m again in 1936.

Phil was born in British Guiana (now Guyana) in 1907, he left for New York at 16. Because he was a citizen of a British colony, he could not compete for the U.S. but was eligible to compete for Canada because of the whole British Empire thing. He joined the Canadian team for the 1928 Olympics, where he won his first medal as a member of the 4x400m relay team. After those Games, he came to Canada to study at McGill University and run on its track team, and then represented Canada at two more Olympics — 1932 and 1936 — in addition to other international events.

In 1934, he became the first Black man to win a gold medal at the British Empire Games (now the Commonwealth Games).

In 1936, he won the inaugural Lou Marsh Trophy, which recognizes Canada’s top athlete, for his performance at the 1936 Olympics.

He became the first Black graduate of McGill University’s medical school and became a respected physician and expert on tropical diseases. He also served in the Canadian army. You can read his Olympics biography here.

Alex Wilson was another Canadian athlete who saw success in this era, with four medals to his name. He was on the same 4x400m relay teams as Phil and he won bronze in the 400m and silver in the 800m in 1932. After his Olympic success, Alex became involved in the NCAA system, working at the athletic director of Loyola University and coaching at Notre Dame. You can read his Olympics biography here.

James Ball was another Canadian athlete to thrived during this period. He took home three medals over two Olympics. He was on the 1928 and 1932 relay teams with Phil and Alex, and he won silver in the 400m in 1928, setting a Canadian record in the process. You can read his Olympics biography here.

John Loaring won bronze in the 400m hurdles in 1936. He also competed in the 400m and the4x400m relay in these Games.

Women finally get to compete in 1928, the world meets the “Matchless Six”

Women got to compete in the Olympics for the first time in 1928.

Canada sent seven women in total to the 1928 Games. Six completed in athletics (the seventh, Dorothy Prior, was a swimmer) and won four medals in the process. They were the most successful women’s team at the 1928 Olympics. These six women would be named the “The Matchless Six” by the Canadian Press after their Olympic success made headlines.

There is also a 2006 kids book called The Matchless Six about them.

In 1928, women were allowed to participate in five athletics events: 100m, 4x100m relay, 800m, high jump and discus throw.

The 4x100m relay team —comprised of Jane Bell, Myrtle Cook, Ethel Smith and Bobbie Rosenfeld — won gold and set a world record.

Bobbie Rosenfeld and Ethel Smith would earn individual medals as well, going 2-3 in the 100m individual event. American Betty Robinson took home gold.

This race is actually available on YouTube:

Bobbie was one of Canada’s first great all-around female athletes. Born in 1903 in Ukraine, she came to Canada with her family a year later. She competed in basketball, tennis, softball, hockey and track & field. She set national records in five different track & field events during her competitive days. At the 1928 Olympics, she ran the 800m in addition to the 100m and the 4x200m relay, and finished fourth. Arthritis would cut her career short. In 1949, she was named the Canadian woman athlete of the half-century by the Canadian Press. You can read her Olympics biography here.

Like Bobbie, Ethel was a versatile athlete who competed in baseball and basketball in addition to track & field. She was born in Toronto in 1907. She would retire from competition after 1929. You can read her Olympics biography here.

Myrtle Cook was born in Quebec in 1910. She achieved a lot of success on track on the national stage, winning six national titles, and setting several national records. She actually held the 100m world record heading into the Olympics — she set it in July 1928 at a meet in Halifax, N.S. — but was disqualified at the Olympics in the finals, thanks to two false starts. After she retired from her competitive career, she became a successful sports writer and was very involved in the Canadian sports scene. You can read her Olympics biography here.

Jane Bell was born in Toronto in 1910. After competing in the Olympics, she moved to the States, where she remained competitive in sports like curling and gold. You can read her Olympics biography here.

Ethel Catherwood was a field athlete and won gold in the high jump, making her Canada’s first female individual Olympic champion.

Ethel was born in the U.S. in 1908 and came to Canada with her family when she was 17. She set the world record in the high jump in 1926, which was broken by Dutch athlete Lien Gisolf in 1928. But Ethel reclaimed her world record title at the Olympics. While the entire team was popular, Ethel was the breakout star and was called the most photographed woman of the 1928 Games. She competed in athletics until 1931, and lived quietly until her death. You can read her Olympics biography here.

In 1932, the 800m was replaced with the 80m hurdles. Javelin was also added to the lineup.

In 1932, Canada would place second in the 4x100m relay, with a team comprised of Mary Frizzell, Mildred Fizzell, Lillian Palmer and Hilda Strike.

Hilda Strike would also win silver in the individual 100m. Hilda, who was born in 1910 in Quebec, had come into the event a favourite to win, but came second to Poland’s Stanislawa Walasiewicz. After Stanislawa died in 1980, it was revealed that she had both male and female sex organs. Her medals and records were not retroactively taken from her, but the revelation caused a media stir (and was ignited again when Caster Semenya’s story made headlines years later). Hilda retired from competition in 1935. You can read her Olympics biography here.

Eva Dawes would win bronze in the high jump.

In 1936, Canada won bronze in the 4x100m, with a team comprised of Dorothy Brookshaw, Mildred Dolson, Hilda Cameron and Aileen Meagher.

Betty Taylor won bronze in the 80m hurdles. Betty competed in the 1932 and 1936 Olympics, and was considered the favourite for gold in 1936. She was a four-time Canadian national champion and held the national record in the event. A photo finish was required to determine first through fourth place in the race, and all four broke the Olympic record. Once the 1940 Olympics were cancelled because of the Second World War, Betty retired from competition. You can read her Olympics biography here.

More events for women were slowly added over the years, but it took a long time to get longer distances back on the Olympic schedule. The 200m was added in 1948. The 800m would not return until 1960. The 1,500m was added in 1972. The 3,000m and marathon were added in 1984. The 10,000m was added in 1988. The 3,000m was replaced with the 5,000m in 1996.

The Olympics of the 1940s were disrupted by the Second World War. Canada didn’t perform well at the Games in the 1950s. We won only one medal in these two decades: bronze in the women’s 4x100m relay in 1948. That team was comprised of Viola Myers Nancy MacKay, Diane Foster and Patricia Jones.

The next wave of success came in the 1960s, with the rise of track star Harry Jerome and middle-distance star Bill Crothers.

The Harry Jerome & Bill Crothers era

I wrote about Harry Jerome’s life and legacy a few issues back. Even though he was a world record holder and one of the best sprinters in the world, he was plagued by injury and won only one Olympic medal: bronze in the 100m in 1964.

Harry wasn’t the only Canadian medallist at the 1964 Games. Bill Crothers won silver in the 800m.

Bill was born in 1940 in Markham, Ont. He would become one of Canada’s greatest middle-distance runners. At one point, he held every Canadian record from the 400m to the 1,500m. He was named Canada’s athlete of the year in 1963. He competed at the 1964 and 1968 Olympics, winning his only Olympic medal in 1964. You can read his Olympics biography here.

Canada wouldn’t win another running medal until 1984. Greg Joy did win silver in high jump in 1976.

The Ben Johnson era

Ben Johnson dominated the sports pages in the 1980s and was Canada’s next big track star. He had a long rivalry with American Carl Lewis that put a lot of attention on their head-to-head races.

But his career ended in disgrace, when he was stripped of his gold medal in the 100m from the 1988 Olympics, when his drug test came back positive.

Ben wasn’t clean, but the sport itself was pretty dirty at the time.

Over the years, six of the eight sprinters who were in the 1988 100m final were implicated in doping at various points in their careers. Ben was banned for two years after his 1988 infraction, but then was banned for life after another positive test in 1993.

This 2018 article from the Toronto Star does a good job of putting the drug use in track — and Ben’s role in it all — in context.

Ben’s medals in 1984 still stand. He won bronze in the 100m and bronze as part of the men’s 4x100m relay with Tony Sharpe, Desai Williams and Sterling Hinds.

1984 was a successful Olympics for Canada, winning five athletics medals in total. In addition to these bronze medals, Canadian women also won silver in the 4x100m relay and silver in the 4x400m relay and a bronze in the 3,000m.

The 4x100m team was comprised of Angela Bailey, Marita Payne, Angella Taylor-Issajenko and France Gareau.

The 4x400m team was comprised of Charmaine Crooks, Jillian Richardson, Molly Killingbeck, Marita Payne and Dana Wright.

Canada’s long distance legacy: Lynn Kanuka and Angela Chalmers

The longest event Canada has medalled in at the Olympics is the now defunct 3,000m.

The 3,000m for women was part of the Olympics from 1984 to 1992, when it was replaced by the 5,000m. The 3,000m for men was only held as a team event at the 1912, 1920 and 1924 Olympics.

Over the three Olympics the 3,000m was held for women, Canada medalled twice: Lynn Kanuka (now Lynn Kanuka-Williams) won bronze in 1984 and Angela Chalmers won bronze in 1992.

Lynn Kanuka-Williams is from Saskatchewan and is one of Canada’s greatest middle-distance racers. Born in 1960, she made her Olympic debut in 1984 in the 3,000m. Between 1983 and 1989 she set 11 Canadian records in distances from the 1,500m to the 10K road race.

She ran both the 3,000m and the 1,500m at the 1988 Olympics.

After she retired, Lynn remained involved in Canadian running as a coach and speaker. She is now Natasha Wodak’s coach.

You can read Lynn’s Olympic biography here.

The 1984 Olympic 3,000m race is known for the showdown between Zola Budd and Mary Decker. Mary was the American golden girl, a hometown hero and gold medal favourite. Zola was an 18-year-old unknown athlete from South Africa. The two got tangled up on the track, causing Mary to fall, crushing her Olympic dreams. The collision and ensuing media attention would impact the rest of both runners’ careers and lives.

If you want to know more about that race, check out the book Olympic Collision by Kyle Keiderling.

If you want a shorter version of the iconic story, check out this Runner’s World article.

Angela was born in 1963 in Manitoba and is a member of the Sioux Birdtail Dakota Nation. She is one of Canada’s best known and accomplished Indigenous athletes.

She competed in the 1988 and 1992 Olympics and competed in the 1,500m and the 3,000m at both Games. She famously dedicated her medal to her father, who passed away in 1984 and never got to see his daughter’s Olympic dreams come true.

She retired in 1996, just before the Atlanta Games, due to a leg injury. She now lives in Australia, where her husband is from.

Angela still holds the Canadian 2,000m and 3,000m records.

Mark McKoy ends Canada’s gold medal drought in 1992

Mark McKoy won gold in the 110m hurdles in 1992, ending a long drought of Canada going without a gold medal on the track.

Mark was born in 1961 and came to Canada as a teenager. He competed in three Olympics Games as a Canadian, 1984, 1988 and 1992. He competed in the 1996 Games for Austria.

After the 1988 Olympics, he admitted to doping and served a two-year suspension. He competed in the 1992 Games clean, and that’s when he earned the title of Olympic champion.

He still holds the world record for the 50m indoor hurdles and the Canadian records for the 110m hurdles, the indoor 50m hurdles and indoor 60m hurdles.

He’s currently a coach and consultant in Toronto.

You can read his Olympics biography here.

Donovan Bailey’s time to shine

Donovan Bailey was the breakout star of the 1996 Olympics, winning gold in the 100m and in the 4x100m relay alongside Robert Esmie, Glenroy Gilbert, Bruny Surin and Carlton Chambers.

I have more on Donovan later in the newsletter, as he’s made the media rounds a lot this summer talking about the 1996 Olympics and racism in Canada.

Donovan still holds the world record for the indoor 50m.

The 2000s: three bronze bright spots

Between 2000 and 2012, Canada won three medals at the three Olympics over this span, all bronze.

The only running medal from 2000-2012 coming from hurdler Priscilla Lopes-Schliep in 2008.

Priscilla Lopes-Schliep won bronze in the 2008 Olympics in the 100m hurdles. She won silver at the same event at the world championships the following year. Priscilla was born in 1982 in Ontario.

She has the genetic condition Lipodystrophy, which impacts how bodies produce and distribute fatty tissue. She spoke about how the condition impacts her life and helped drive her toward athletic excellence in this 2010 interview with Spikes magazine.

She failed to qualify for the 2012 Olympics and is now a public speaker.

We also got a field medal in 2008, thanks to a bronze in shot put courtesy of Dylan Armstrong.

Another field medal came in 2012, when Derek Drouin won bronze in the high jump.

We almost won bronze in the 4x100m relay in 2012, but Canada was disqualified for a lane violation.

In 2004, Perdita Felicien was the favourite to win gold in the 100m hurdles. She was the 2003 world champion and 2004 world indoor champion, but she infamously fell over the first hurdle at the Olympics. She didn’t compete in the 2008 Olympics because of a foot injury and didn’t qualify for the 2012 Olympics. She retired in 2013 and is now an active sports analyst and broadcaster. Her memoir, My Mother’s Daughter, is coming out next year.

Andre De Grasse ushers in a new era

Then 2016 was the best Olympics Canadian athletics had seen since 1928. We won six athletics medals, and Andre De Grasse emerged as Canada’s next track star.

In addition to Andre’s three medals (silver in the 200m, bronze in the 100m and bronze in the 4x100m relay with Akeem Haynes, Aaron Brown, Brendon Rodney and Mobolade Ajomale), Canada won bronze in the decathlon (Damian Warner), bronze in the heptathlon (Brianne Thiesen-Eaton) and gold in the high jump (Derek Drouin).

I won’t go deeper into these athletes and their accomplishments, because I write about them a lot in this newsletter already.

Canada’s history in combined events

Before Damian and Brianne’s medals, Canada had previously only won two medals in combined events: Frank Lukeman won bronze in the pentahlon in 1912 and Dave Steen won bronze in the decathlon in 1988.

Frank was an athlete from Montreal. He originally finished fourth in the pentathlon at the 1912 Games, but American Jim Thorpe was disqualified months after the Games because he had played professional baseball and was therefore not an amateur athlete.

His disqualification was eventually overturned in 1982 because the International Olympic Committee and Amateur Athletics Union did not correctly follow the procedures for disqualification. However, the medallists, including Frank, were permitted to keep their upgraded medals.

Frank would go on to serve in the First World War, after which he returned to Montreal and lived there until his death in 1946. You can read Frank’s bio on the Canadian Olympics site here.

The pentathlon for men was held in the 1912, 1920 and 1924 Games. It consisted of long jump, javelin, 200m, discus and 1,500m.

In 1928, the pentathlon was dropped in favour the the decathlon, with the 10 events we see in the Olympics today. The decathlon has been part of the Olympics since 1912.

Women’s pentathlon was added to the Olympics in 1964 and was expanded to the seven-event heptathlon in 1984.

Dave Steen gave Canada our second combined events medal in 1988, when he won bronze in the decathlon.

Dave, who was born in 1959 in British Columbia, competed in the 1984 and 1988 Olympics in the decathlon. In 1984, he placed eighth, which was considered a disappointment. He rebounded to take bronze in a close competition in 1988.

After his retirement from sport, Dave moved to Ontario, became a firefighter and became an outspoken advocate for clean sport. You can read more in his Olympics biography.

30 years after Dave won bronze, the gold medallist, Germany’s Christian Schenk, admitted to drug use.

"I don't feel as if anything was taken from me, I really don't," Dave told CBC Sports in 2018. "You need to internalize your results and try to figure out how to feel good about doing the best that you can, but still coming up short compared to other people who are cheating. That's a tough thing to do, and it's learned and it takes a little while to get in that head space."

What’s next?

The next Olympics are a year away, in Tokyo in 2021, if the coronavirus can be contained. Canadian track & field has been on an upswing the five years, thanks in part to an investment in Canadian sport because of the Toronto PanAm Games in 2015 (I wrote about that legacy here).

We have several stars who had their best ever years in 2019. Moh Ahmed won Canada’s first distance medal at a world championships when he won bronze in the 5,000m and he has openly spoken about his quest for gold. Gabriela DeBues-Stafford broke nine Canadian record last year and is set to join one of the best training groups in the world, the Bowerman Track Club, when it is safe to do so. Andre De Grasse has recovered from the injuries that plagued him since Rio and is aiming to nab the only medal colour that eludes him so far: gold. 800m runner Melissa Bishop-Nriagu wants redemption from finishing a heartbreaking fourth in 2016. We have field stars who can compete on an international stage. Things look good for Canada heading into the next Olympics. We just need to world to get safe enough to host them.

The qualifying window for marathoners for the 2020(1) Olympics has been extended

Before the Olympics were postponed, the qualifying window for the marathon and the racewalk was Jan. 1, 2019 to May 31, 2020. The qualification process was complicated, and athletes could qualify through points or time. I broke it all down in March of 2019.

Then the pandemic started, the Olympics were postponed and World Athletics announced that the qualifying window for the 2020(1) Olympics was being put on pause, meaning performances that occurred between April 6 and Nov. 30, 2020 would not count towards qualification or towards points for qualifying later. The window was set to re-open on Dec. 1, 2020 and run to May 31, 2021.

This past week, World Athletics changed their stance on that for the longer events. The qualification period for racewalking and the marathon will re-open on Sept. 1, 2020.

If races can happen safely, this is ultimately a good move because it means marathoners will have two cycles to try to gut out an Olympic qualifying performance: fall 2020 and spring 2021.

However, the pandemic makes reality uncertain and several fall races are already cancelled. Will races make riskier decisions as a result of this change?

Hope for the London marathon

There’s now incentive for London — the only world major not yet cancelled/reduced to elite only because of COVID — to put on an elite-only race. In fact, World Athletics specifically shouts out London in their announcement:

The Virgin Money London Marathon, due to take place on Sunday 4 October, is committed to working with World Athletics to promote this opportunity to athletes around the world and to assist with their travel challenges so they can participate in London and achieve their Olympic qualifying time.

London was originally set for April 20, 2020. It had several elites on the starting line, including an anticipated showdown between Eliud Kipchoge and Kenenisa Bekele the only 2:01 marathoners in the world. It was also going to serve as a qualifier for British marathoners for the Olympics.

Four elite Canadians were set to run London back in April: Kinsey Middleton, Tristan Woodfine, Evan Esselink and Ben Preisner.

Then London was postponed to Oct. 4, 2020.

The London marathon put out a non-announcement last week, saying they were working with the UK government to come to an agreement and we would know what is happening no later than Aug. 7.

I don’t know how elite contracts are impacted by postponements. I also don’t know how quarantine will work for international athletes, if Canadians can or will race London when we know what it happening. But we may soon find out.

More hope for Canadian marathoners

The pandemic isn’t as bad in Canada as it is elsewhere in the world. Which could mean that small Canadian races might actually happen. And races that aren’t cancelled may see top-tier Canadian talent come out to chase a qualifying time.

Fall races in Canada in this position include the Manitoba Marathon (currently scheduled for Oct. 11, postponed from June), the Blue Nose marathon in Halifax (currently scheduled for Nov. 8, postponed from May, although running a fast time on this course is a FEAT) and the Valley Harvest in the Annapolis Valley in Nova Scotia (Oct. 11).

The Manitoba marathon hosted the Canadian half-marathon championships in 2019, so it has experience with Canadian elites looking for a high-caliber race. (They were supposed to host the championships again in 2020, but they will not be part of the postponed version of the event.)

However, several other marathons of similar sizes across Canada have already been cancelled. So it’s not a guarantee these races will even take place.

Who can make the Canadian Olympic marathon team again?

Canada currently has four women and one man qualified for the 2020(1) Olympic marathon. We can send up to three athletes of each gender.

Dayna Pidhoresky and Trevor Hofbauer got automatically selected when they won the Canadian marathon championships in 2019 with winning times under the qualifying standard.

Athletics Canada will pick the two other team members for each gender from the other qualified athletes.

Rachel Cliff qualified with her national record-setting run of 2:26:56 in Nagoya, Japan, in January 2019. Malindi Elmore qualified when she broke Rachel’s record, running 2:24:50 in Houston in 2020. And Lyndsay Tessier qualified when she placed ninth at the world championships in Doha 2019.

Moh Ahmed is getting the attention he deserves after a stellar summer

Canadian Press profiled Moh Ahmed in the wake of his stellar intrasquad performances with his training crew, the Bowerman Track Club.

The 29-year-old trains in Portland, Oregon and became the first Canadian to win an international distance medal in 2019, when he took bronze in the 5,000m at the world championships in Doha. This set him up well for 2020, an Olympic year, until the pandemic happened, things got cancelled and professional runners had to get creative.

Bowerman Track Club scheduled a series of intrasquad meets that had 🔥performances from everyone, and saw American records, Canadian records, North American records and even a world record fall.

Moh broke the Canadian 5,000m record at one of them, and became the fastest North American and the 10th fastest in the world with his 12:47.2 time.

"I was doing the math, I was looking at the clock, I was like, 'OK, I'm on pace, I can do this.' I was very focused. I was very much in the zone," Ahmed said. "More than anything it was the internal [dialogue]. It was the plan that I had laid out beforehand, and the various little cues, words that I needed to use at various different distances."

In another one, he ran 3:34.89 in the 1,500m to become the fifth fastest Canadian at the distance.

In the piece, he talks about his disappointment at the Olympics being postponed, but focusing on what he can control while looking forward to 2021:

"This year could have been my year, but next year, and the next year, and the next year after that could also be my year," Ahmed said. "It's a confidence booster, if you are dreaming about getting medals and rubbing elbows with the best in the world you have to be capable of those sort of times. And for me to validate that, albeit in a very controlled and a relaxed atmosphere, it validates the dreams and expectations that I have for myself."

Moh was also the co-host of a recent episode of Canadian Running’s The Shakeout podcast. He talked more about these stellar performances, his life training with the Bowerman Track Club and more. You can listen to that episode here.

Bowerman Track Club is racing one more time, according to that episode, on Friday.

Donovan Bailey has been an Olympic champion, and has speaking out about racism in Canada, for 24 years

On July 27, 1996, Donovan Bailey won Olympic gold and set the world record in the 100m, when he ran 9.84. He still co-owns that record with Bruny Surin.

But, before he won gold and set the world record at the Olympics in the 100m, he spoke out about racism in Canada in Sports Illustrated, and paid for it.

A few weeks ago, Donovan Bailey spoke to Maclean’s magazine about racism in Canada. It’s a comprehensive piece that looks back over the past 24 years of Donovan’s career, the price he paid — and is still paying — for speaking out in 1996, and why he’s still speaking up:

Bailey is still bothered that few people—and none from Athletics Canada or the COC—took the time to ask him why he spoke out about racism in Canada. Their top athlete and global superstar had a concern and nobody cared to ask. Instead, his superiors railed at him for “startling and unfounded” criticism, he says. And, he believes to this day, “they boxed me out.” He’s never been asked to lead a track and field team to any games, like the Pan Ams, Commonwealth or Olympics; there’s been no coaching assignment, no ambassadorial role, no promotion for endorsement deals.

Do you see Hockey Canada treating Wayne Gretzky that way? Or Basketball Canada going for two decades without trying everything to get NBA star Steve Nash on their corporate sports team?

Donovan Bailey, arguably the most successful track Canadian athlete of the past 50 years, still has been not named to the Order of Canada. Post Media had a good column by Steve Simmons about why that’s embarrassing for our nation.

Donovan sees this moment as a pivotal one for this country. From the Maclean’s piece:

Bailey senses an urgency and a determination to push the envelope now because Canadians may stop listening tomorrow. “We cannot only speak,” says Bailey. “We must take an active part to create structures so we don’t have to have this conversation going forward. We are all fathers; all successful Black men. We have to make a move. We all have to do more than just talk.”

Aaron Brown interviewed Donovan about his 1996 experiences for an episode of SportNet’s Athlete2Athlete. They talk about Donovan’s experience of speaking out about racism back then, setting the world record and more:

Donovan also stopped by the Luca Rosano Show to cover much of the same topics, but it’s still worth checking out:

Strides: other stuff to know about

🏟Athletics Canada has launched a virtual challenge open to all Athletics Canada members. From August 3 to August 24, athletes can compete in 11 events: 100m, 200m, 400m, 800m, 1,500m, 3,000m, standing long jump, long jump, triple jump, shot put and discus. Competitive categories include U14, U16, U18, U20, open, and Masters 35 to 100, along with para athlete categories. To find out more, or to register, you can check out the Athletics Canada website.

👟CBC Sports asked the question: how fast could a regular person run 100m? They got Andre De Grasse to help, found a regular Joe and put it to the test. You can watch the video and find out the result for yourself here.

🎧Dr. Janice Forsyth, an academic and author of the book Reclaiming Tom Longboat, was recently on the Burn It All Down podcast to talk about her book and the history of Indigenous sport in Canada and how events like the North American Indigenous Games play an important part in giving young people and opportunity to connect with their culture and identity. It’s not running specific, but it’s a must listen for anyone who is interested in equity and reconciliation in Canadian sport.

🌎Lazarus Lake announced his latest virtual challenge: a circumpolar race around the world. The 40,000km race is for teams of up to 10, and they have 16 months to complete it, in 12 stages. Canada, “the Great White North” in this race, is stage 11 There’s also a multi-sport option for teams up to five members. It begins on Sept. 1 and runs through Dec. 31, 2021. If you’re interested, you can sign up here.

🙏Canadian marathon champion Dayna Pidhoresky wrote a column for iRun looking back on the moments in her career she’s most thankful for. She reflects on her first ever ribbon for running, her high school track experience, her solo runs early in her career and, of course, qualifying for the Tokyo Olympics and being named the national marathon champion.

🎧Racewalker Rachel Seaman was on the Women Run Canada podcast. Rachel owns five Canadian records and is the top female racewalker in the country. The conversation is a really good, as Rachel talks about her mental health struggles, how an injury prevented her from competing in the 2016 Olympics and what her comeback to Tokyo 2020(1) has been like. Listen to the conversation here.

🎬The HBO documentary The Weight of Gold is now available in Canada, on Crave. It’s about the pressures elite athletes, especially successful ones, face. Only one runner, American hurdler and bobsledder Lolo Jones, is in the film, but it features several athletes who have bene open about their mental health struggles, including swimmer Michael Phelps, figure skater Gracie Gold, snowboarder Shaun White and more. If you have a subscription to Crave, you can watch it here.

🏃🏿♀️The International Olympic Committee is considering adding a mixed gender cross-country relay event to the 2024 Olympics. A decision will be made later this year, but it remains to be seen what other events will be cut to include this one, to keep the number of events and athletes at the Games consistent.

🌟Canadian Running has partnered with UnderArmour to out together a series about improving your own running. It’s called Your Better Running Self and you can check it out here.

🏜A decade after the book Born to Run ignited the minimal running craze (remember that?!) Canadian science and running writer Alex Hutchinson looks at changing the narrative Western white runners tell about the tribe at the centre of that book, the Tarahumara of Mexico, for Outside magazine. Basically, Alex posits that if a culture values something, they get good at it, including long-distance running. As Canadians, we should know this, just look at hockey in this country.

📝If you run with a run crew or group (or did before COVID), please take some time to fill out this survey for a research project at the University of Manitoba, about how the pandemic has affected your running habits. I did the survey and subsequent interview and it was interesting reflecting on how the past few months have shifted my relationship with running. Also, science is cool.

That’s it for this week!

If you’re reading this online or it was forwarded to you by a friend, you can subscribe below:

Run the North comes out on Mondays — except when Monday is a holiday, like this week, then it comes out on Tuesday.

If you want to reach out for any reason, you can email me at runthenorthnews@gmail.com.

Thanks for reading and keep on running. I’ll see you next week!