Who should be Canada’s athletes of the year?

Athletics Canada announced the finalists for their athletes of the year awards, so I make some wild guesses about who is going to win.

Who should be Canada’s athletes of the year?

Athletics Canada announced the finalists for their 2018 athletes of the year awards. Three finalists were revealed in each of the 13 categories, recognizing performances from Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2018.

Overviews of six of the awards below. I can’t find the date for when the winners will be announced, but I will share that information once I know it, so we can see how wrong I was.

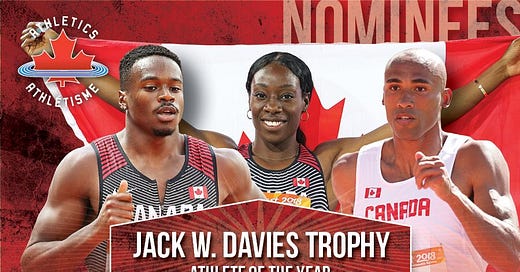

Athlete of the year

Sprinter Aaron Brown was the Canadian champion in the 100 (10.16) and the 200 (20.17). He took home two medals at the NACAC championships: silver in the 200 (20.20) . and gold in the 4x100 (38.56). He also won silver in the 200 (20.34) at the Commonwealth Games and was ranked 12th in the world at the distance.

Long jumper Christabel Nettey won the national championship (6.21m) and gold at the Commonwealth Games (6.84m). She placed seventh at the world championships and scored a handful of top eight finishes as various meets around the world.

Combined events athlete Damian Warner was dominant in 2018. He set two Canadian records in 2018: he scored 6,343 points and took home silver in the heptathlon at the IAAF World Indoor Championships and scored 8,795 points and won gold in the decathlon at the IAAF Combined Events Challenge. He was also ranked second in the world in both events.

My pick: Two Canadian records and a world championship medal put Damian on top here.

Outstanding performance of the year

As stated above, Damian Warner set two Canadian records in 2018, in the heptathlon and the decathlon.

Pole vaulter Alysha Newman set a Canadian record at the Commonwealth Games, clearing 4.75m. The performance also scored her a gold medal and was a Commonwealth Games record to boot.

Marathoner Cameron Levins broke the 40-year-old Canadian marathon record in 2018. He ran 2:09:25, good for fourth place at the Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon.

My pick: Damian’s 2018 is impressive, but you don’t kick off a comeback the entire running world has been waiting for by breaking a 40-year-old Canadian record and not win this prize. It’s going to Cam.

Off-track athlete of the year

Race walker Evan Dunfee finished 2018 ranked 20th in the world in the 50K race walk. He won gold in the 20K at the NACAC championships and placed eighth in the same distance at the Commonwealth Games.

Long-distance runner Rachel Cliff won the Canadian 10K championships, running 32:23, and won the Woodlands half-marathon in 2018, with a Canadian record time of 1:10:08. She also placed 11th at the Berlin marathon, running the fastest Canadian marathon debut and the fourth fastest marathon time by a Canadian woman at the time, 2:28:53.

Cameron Levins probably had the athletics performance of the year in 2018. His 2:09:25 fourth-place finish at the Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon broke the 40-year-old Canadian marathon record and was a comeback story for the ages.

My pick: Cam will take performance of the year, but Rachel’s 2018 is more well-rounded, so she gets the edge here.

Track athlete of the year

Mohammed Ahmed took home silver in the 5,000 (13:52.78) and the 10,000 (27:20.56) at the Commonwealth Games. He was the Canadian champion in the 5,000 (14:36.09) and finished the year ranked 4th in the world in the 5,000 and 10th in the 10,000.

Aaron Brown was the Canadian champion in the 100 (10.16) and the 200 (20.17). He took home two medals at the NACAC championships: silver in the 200 (20.20) . and gold in the 4x100 (38.56). He also won silver in the 200 (20.34) at the Commonwealth Games and was ranked 12th in the world at the distance.

Brandon McBride was ranked fifth in the world in the 800. He won gold at NACAC at the distance (1:46.14), silver at the national championship (1:46.42) and set the Canadian record at the Diamond League meet in Monaco (1:43.20).

My pick: Aaron Brown won the most and had the strongest Diamond League performances (five top five finishes). But setting a Canadian record is always hard to top. I think Aaron’s more complete resume, though, gives him the edge over Brandon.

Wheelchair athlete of the year

F53 thrower Pamela LeJean won three national championships, in shot put, discus and javelin and set Canadian records in discus (4.76m) and javelin (12.83m). She’s ranked second in the world in all three events.

T53 sprinter and middle-distance specialist Jessica Frotten won three national championships, in the 400, 800, 5000 and finished second in the 1500. She won a silver in the 400 and bronze in 200 and 800 at the World Para Athletics Grand Prix. She wrapped up 2018 ranked third in the world in the 5000, fourth in the 1500, fourth in the marathon and fourth in the 800.

T53 sprinter and marathoner Brent Lakatos won the Berlin marathon in 1:29:41. He also won national championships in the 800 and 1500. He placed 10th at the London marathon. He was ranked first in the world in the 800, 1500 and 5000 and second in the 400 and the marathon.

My pick: Brent Lakatos won a world major and can compete in every distance out there. His strong international showing and versatility is what will give him the edge here.

Canadian university athlete of the year

Thrower Sarah Mitton won the U Sports title in shot put (15.09m), came second in the weight throw (17.79m). She set the U23 Canadian shot put record (18.52m) and placed second in the shot put at the Canadian national championship (17.05m).

Middle-distance runner Julianne Labach won the U Sports title in the 1000 (2:43.96) and placed third in the 600 (1:29.81) She also placed fourth in the 800 (2:02.07) at the Canadian national championships.

Middle-distance runner Kelsey Balkwill won three U Sports national titles, in the 300 (38.46), 600 (1:29.37) and 4x400 (3:42.88). She also placed seventh in the 400 (53.14) at the Canadian national championships.

My pick: Since this is an Athletics Canada award and not a U Sports award, I’m going to go with the athlete with the strongest national showing, Sarah Mitton.

Canada takes home one medal at IAAF world relay meet

The Canadian mixed team at the IAAF mixed World Relays is coming home with a silver medal and a national record.

The team, comprised of Austin Cole, Aiyanna Stiverne, Zoe Sherar and Philip Osei, ran 3:18.15 in the final. USA placed first and Kenya came third.

The national record of 3:16.78 was set during the preliminary rounds, Canada won their heat with that time.

The 4x400 women’s team at the same meet placed fourth with a time of 3:28.21. Maya Stephens, Madeline Price, Alicia Brown and Sage Watson ran for Canada. Poland won gold, USA won silver and Italy won bronze.

Neither the Canadian men’s or women’s 4x100 teams made it to the final.

CBC Sports has a good recap of all the results from the meet, which took place over the weekend in Yokohama, Japan.

Radio-Canada made a documentary about record-setting wheelchair team Sebastien Roulier and Marie-Michelle Fortin

Marie-Michelle Fortin was born with cerebral palsy and has used a wheelchair her entire life. Her running partner, Sebastien Roulier is a pediatrician and ultrarunner. When Marie-Michelle, who is from Chicoutimi, heard about the Quebec-designed Kartus wheelchair, which would enable her to experience running, she was determined to get one for herself. The twosome ran the 2018 Demi-Marathon Oasis de Lévis together, completing the half-marathon in 1:30:37. Their second race together was the 2018 Montreal Rock ‘n’ Roll Marathon, where they broke the wheelchair team world record with a finish time of 3:01:24. This performance qualified them for Boston in 2019.

The 13-minute documentary is entirely in French, but even if your French isn’t that great, the emotion comes across loud and clear.

Canadian Running wrote a rough English translation of the doc, if you’d like.

Anson Henry explains the new IAAF qualifying process for the Olympics

CBC wrote a story about how Canadian athletes in track & field are trying to qualify for Tokyo 2020.

If you read this newsletter regularly, you already got the gist of it, but CBC recorded this video with Anson Henry explaining the new system. He focuses on the world ranking aspect of qualifying, and it’s very helpful.

T38 runner Nathan Riech sets two world records

T38 sprinter Nate Riech has broken two world records in the past two weeks.

On May 3, Nate broke the 1500 record, running 3:57.84 at the Portland Twilight meet. This was another instance of Riech breaking his own record, it previous was 3:57.92.

On May 12, he broke his own world and Canadian record in the 800 at a meet in Los Angeles. Nate ran 1:56:18, topping the previous record of 1:57.78

T38 is a classification for athletes with impairments that affect coordination and muscle movement, such as cerebral palsy and ataxia.

The National Post profiled Nate last year, when he set the double 800-1500 world records for the first time.

He was 10 years old when he suffered the injury that would set all this in motion:

Riech was just 10 when he was playing golf with some buddies in Phoenix, where the family lived. A group behind them was playing through, and so Riech and his friends took refuge from the hot sun under a tree to wait. But someone fired a drive from 150 yards away that veered left, hitting Riech in the back of the head.

“It actually hit me so hard it was more of a numbing feeling, a tingly sensation going through my body,” Riech said. “At first, I didn’t honestly know I got hit until my friend was like ‘Dude, you just got hit,’ and we saw a ball bounce off in a weird direction.”

He’s from an athletic family and got into running as a teenager, even running for Furman University against able-bodied athletes.

He’s a dual Canada-U.S. citizen who chose to compete for Canada because it was his Canadian mom who was by his side for all his treatment sessions after his accident.

He’s crushing records, but he’s working really, really hard to make it happen:

But if it seems like success comes easy for Reich, it doesn’t. He keeps a gruelling schedule of hours of foam rolling and stretching daily. His rewired brain has to work significantly harder than able-bodied athletes, almost like a rowing eight crew that’s missing a few oarsmen. His brain works so hard to run, his mom said, that it takes him twice as long as an able-bodied athlete to recover.

“I notice it the most in the last lap of a race,” Reich explained. “When I set the 1,500 world record, with 50 metres left I thought I was going down. All of a sudden my hip stopped working, and my arms were flailing.

“Because I have a hole in my head, most people don’t have to think about using the right side of their body, but I have to tell the right side of my body to move, especially my arm, I have to say “use it, use it, use it.” And then late in the race, you don’t want to think about that, you want to be naturally doing it. But I have to constantly think about getting my hip up and driving my knee.”

Strides: Links worth reading

→ iRun profiles Silvia Ruegger, the former Canadian record holder who was diagnosed with cancer a few years ago. Her marathon record of 2:28:36, set in 1985 at Houston, stood for 28 years. Running and her faith have been pillars of Silvia’s entire life:

Nancy Ralph, a friend for over 30 years, has also witnessed Ruegger’s unrelenting faith.

“All of the disciplines she developed as a runner serve her as a cancer survivor. Everything in her life before that diagnosis prepared her for the battle that she has waged against this cancer,” says Ralph. “She has been utterly convinced that God would eradicate cancer from her body and she was equally determined to do her part in the marathon of recovery. Hand in hand with Silvia and her medical team, God has been enthroned above this furious flood.”

→ Women’s Running has a story from Heather Mayer Irvine about running with her mother, in honour of Mother’s Day:

The first time she felt that mid-race dizziness she was scared. When I found out she hadn’t eaten anything during those 13.1 miles, I gave her a crash course on race fueling. And also offered a bit of her old advice: Don’t push too hard.

The next time it happened, my mom knew what to do.

“I knew I’d be okay if I slowed down and ate something,” she told, me after the race.

In the peak of fitness, I run for time, for the tape. My mom runs for the medal — she sends me pictures saying Michael Phelps and his 28 pieces of Olympic hardware should “move over.” She runs for the ecstasy of crossing the line no matter what the clock says, because “I love making you proud, Heather.”

→ Runner’s World profiled George Etzweiler who, at 99 years old, is still running regularly:

George is racing without his Mountain Men today. It’s one of his three annual races beyond the relay, the Mountain Washington Road Race in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. The 7.43-mile road climbs up more than 5,000 feet to the tallest point in the Northeastern United States.

From the start, George falls to the back of the pack with his grandson, Bob, who acts as a pack mule carrying jackets and George's homemade lemonade—the only thing he consumes while running. Every runner goes by him, many taking pictures or wishing him luck: “Go, George.” We love you, George.” “You’re an inspiration, George.”

The word inspiration troubles George: “I haven’t died yet.” People see an elderly runner beating back age through a measured shuffle. Yet people don’t see his entire story. They don’t see him calling elderly runners to reignite the flame inside them when they think they’re done. They don’t see the champion of the everyday runner, who could have quit years ago. When he retired in 1993. Or when Mary passed away. Or even after this, his 13th time racing up Mount Washington.

But they do see a hero, an icon, charging up the mountain until he finishes in 4:04:48 — a minute faster than last year.

→ Katherine Turner wrote about female runners and periods for Strava. This stuff matters. I include my periods in my training logs for my coach and she thanked me for feeling comfortable enough to share that with her. Uh… what? If I feel like garbage during a workout because I’m menstruating, my coach should know that. That’s different than being sick or injured or overtrained. And if my cycle is expected on the same day as a key workout, my coach should know that. But I know 1) I have no filter and 2) I’m lucky to have a female coach who gets this stuff.

I, like many female athletes I know, fell into a trap of believing that it would all just be easier without periods. And that they didn’t matter that much anyway. Periods were inconvenient things to be bemoaned, not celebrated. They seemed to signify that my body was changing — was becoming more ‘womanly’, was rounding and softening in a way that felt like the antithesis of all the hard work I’d put in. Periods meant gaining fat and slowing down; they weren’t for athletes, right?

I started under-fueling my training creating a dramatic mismatch between the energy I was taking in and the energy my training was demanding. My body shut down my menstrual cycle in an attempt to preserve energy and I didn’t get a period for eight years, a condition known as amenorrhea. I thought, at least at first, that I was doing something right. That not having a period meant that I was truly an athlete. Now, multiple stress fractures down the line, as a result of the adverse impact of low estrogen on bone health, I know that having a regular period is as much a marker of training health as fast times and medals.

→ Lauren Peterson, who was a speechwriter for Hillary Clinton, wrote about becoming a runner while working as a speechwriter — a chaotic, time-consuming and stressful job:

Kathrine Switzer, one of the first women to run the Boston Marathon, said, “If you are losing faith in human nature, go out and watch a marathon.” Nothing tested my faith in people like the 2016 election, and nothing restored it like running. I watched strangers in parkas cheering for runners in the Wisconsin snow.

When I ran a race in New York’s reddest county covered in Hillary Clinton stickers, a woman with a Trump yard sign offered me an orange slice at mile 16.

After the worst day of my life — November 8, 2016 — the first time I felt human was when I dragged myself out of bed and went for a run. If I hadn’t, I might have missed the messages kids from our adopted neighborhood in downtown Brooklyn left on the sidewalk in chalk: “Keep fighting!” “Girl power!”

And one Saturday in Brooklyn, I planned a long run to end at a jewelry store so I could buy an engagement ring for my girlfriend, Liz.

Running has brought more than escape to my life. It has brought me joy, painfully tight calves, a left knee that aches when it rains, and a perpetual sock tan. It also taught me some valuable lessons: Do explain to your co-workers why you’re going to leave every day and come back sweaty. Don’t try to check your work emails during a race. Never put “Signed, Sealed, Delivered” on your running playlist unless you’re ready to cry about how much you miss Barack Obama. Most of all, even if you can’t run away from your problems, you can definitely run through them.

→ Scott Douglas wrote about the connection between running and mental health for Runner’s World:

Most Tuesdays, I run early in the morning with a woman named Meredith. For such close friends, we’re quite different. Meredith is a voluble social worker who draws energy from crowds. I’m an introverted editor who works from home. Meredith runs her best in large races and loves training with big groups. I’ve set PRs in solo time trials and tend to bail when a run’s head count gets above five. Meredith is a worrier, beset by regrets and anticipated outcomes, who has sought treatment for anxiety. I have dysthymia, or chronic low-grade depression. We like to joke that Meredith stays up late as a way of avoiding the next day, whereas I go to bed early to speed the arrival of a better tomorrow.

We do have one key thing in common: Meredith and I run primarily to bolster our mental health. Like all runners, we relish the short-term experience of finishing our run feeling like we’ve hit reset and can better handle the rest of the day. What’s not universal is our recognition that, without regular running, the underlying fabric of our lives—our friendships, our marriages, our careers, our odds of being something other than miserable most of the time—will fray. For those of us with depression or anxiety, we need running like a diabetic needs insulin.

The book to read this week

How Bad Do You Want It by Matt Fitzgerald is one of the best sports performance psychology books I have ever read. The secret is that Matt uses each chapter to tell the story of one elite athlete (some are runners, but others are triathletes and cyclists) to look at one aspect of performance — such as choking, overtraining, longevity, etc. — and then uses that singular story, combining it with science and psychology to extrapolate lessons for other athletes absorb. It’s super readable and the athletes and stories he chooses to highlight are just as interesting as the takeaways you get.

The final kick

That’s it for this week!

I want to wrap with a shout-out to my mom, who, when I asked her to come to my first marathon, replied, “You want me to watch you run for FOUR HOURS? That sounds boring.”

Thanks for always keeping it real, mom. Happy belated Mother’s Day, in a newsletter you don’t read.

If you want to reach out for any reason, you can find me at runthenorthnews@gmail.com. Thanks for reading and keep on running.